image: New York magazine

I do not know every detail of every one of those 35 women's stories, but I don't have to. I have made the purposeful decision to believe the words of 35 women over the words of their one accused rapist.

Over the past few months, once-beloved TV father figure Bill Cosby has been in the news due to allegations that he drugged and raped more than 35 women over the course of several decades, going as far back as the 1970s. At first, it seemed that most people were reluctant to believe the accusations. Over and over again, his defenders asked, "Why didn't they report it when it happened?"

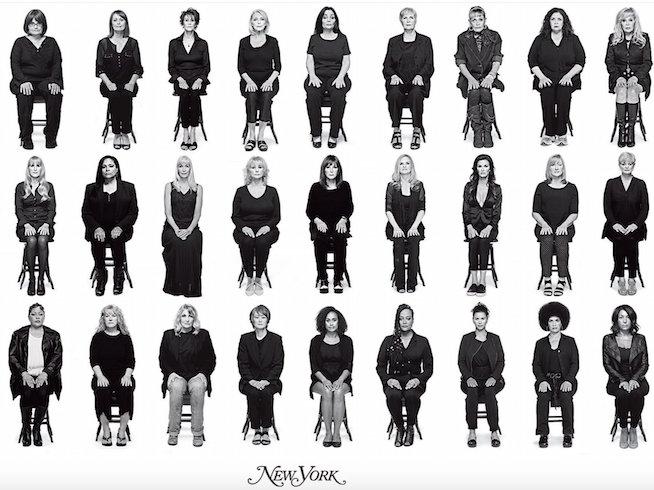

Some of his accusers actually did report their rapes, and the details of Cosby's deposition in 2005 have recently come to light. Earlier this week, New York Magazine published an astonishing account of 35 of the women who claim to have been raped by Cosby. Many of them said that they were told that no one would believe them, and so they remained silent.

I didn't report my rape, either.

My mom told me I should. She also told me that I shouldn't have showered afterwards. It was too late for a rape kit by the time I made my way home from a high school sleepover, and I couldn't imagine telling my story to a doctor, much less a police officer.

The thing about trauma is that it is hard to remember many of the details, even though some of them remain eternally etched in your memory. I will never forget the pattern of my friend's curtains that I stared at all night long, willing the sun to rise so I could go home, and I will also never forget staring at the white liquid in my underwear and then standing in the shower, trying to burn away my skin, until the water became icy cold.

What I don't remember is exactly what happened. I remember going to a sleepover and discovering that my friend's mom was having a party. I remember being uncomfortable with the adults drinking, but I wasn't scared. We went for a walk to get away from the party, but a group of men followed us. Or maybe they were already outside. I don't remember who or even how many men forced themselves on me, but I do remember my friend telling me to stop making such a big deal about it. She had already had a few abortions by then, and she eventually left school after telling me that they were her stepdad's babies.

If I had reported my rape, I wouldn't have been able to provide investigators with many details beyond where it happened. I couldn't have picked my rapist — or rapists — out of a lineup, and I couldn't have even told anyone exactly what they did to me. I washed away all of the evidence in that scalding shower, and I would have rather died than left their remnants on my body long enough to collect it. If I had been put on trial (and let's face it, rape victims are always put on trial), my story would have been vague and murky, and I would have been deemed an unreliable witness to my own rape.

I don't remember exactly how old I was when I was raped, but it's been more than 20 years now. A few years ago, I began to suffer from flashbacks almost every day for six months. I felt every sensation, as if it was happening to me all over again, even though the details remained fuzzy. It was like being raped night after night, again and again, and I had no idea how to control the flashbacks or why they suddenly began.

I was fine, I thought. I had dealt with it, I thought. But what I had actually done was deny its impact on me, and refuse to experience the helplessness, terror, and even rage that I felt that night. I bottled it up, and stuffed it tightly inside, and rarely even thought about it. Until finally, it left me no choice.

It's easy to say that rapes should always be reported to the police, and that the accounts of rape victims should be questioned. Their stories, unlike their accused rapists, are often inconsistent. Their vagueness can seem unreliable. But that is the nature of trauma, and rape is trauma.

Even now, so many years later, it took 35 women standing together and the power of social media to begin to turn the tide against Cosby. No one leapt to tell that first woman that they believed her experience; it took 35 women before the public was willing to even consider that their favorite TV dad was a serial rapist. Most women do not have 34 others standing in the wings, and most women have every reason to expect that reporting their rape will lead to nothing but invalidation, re-victimization, and even humiliation for them and little to no consequences for their rapist.

When my daughters told me that they had been sexually abused, I made sure that this time I did the right thing. They were interviewed by police and I even held down my screaming four-year-old so that a nurse could photograph the bruises on her inner thighs that were just about the size of a man's thumbs. When the prosecutor told me that there wasn't enough evidence to arrest their molester, I refused to accept it, and I sent letters until she agreed to meet with me to discuss it. It was at that meeting that she told me that, unless a completely neutral third party witnessed the abuse, she wouldn't take it to trial. "I don't try cases I can't win," she said. She didn't want to "put the girls through that," she told me.

My daughters and I together make four. Their sexual abuse was reported, mine was not. But none of the men who harmed us have ever spent even a single day in jail for what they did to us. Reporting their sexual abuse did nothing except traumatize them even further. And our abusers weren't even powerful, famous men like Cosby. They were just average men, and somehow they began from the standpoint of their stories being true while we began from the standpoint of being liars.

The same was true for the 35 women who accused Cosby of rape. No one believed them individually but, even worse, no one seemed to truly believe them until the depositions from 2005 lent "proof" to their allegations. Or, to put it simply, until Cosby himself largely confessed to inappropriate sexual behavior. His word, even while confessing to giving women drugs to have sex, was more believable to the American public than the words of 35 individual women.

In a country where it's estimated that only 6% of rapists are ever sent to jail, the Cosby accusers, my daughters, and I are in the dramatic majority. Despite what we all might want to believe, justice for rape and sexual assault victims is extremely rare. Deciding when and if to report a rape is a highly personal decision, and it has absolutely no bearing on the veracity of the accusations.

I do not know every detail of every one of those 35 women's stories, but I don't have to. I have made the purposeful decision to believe the words of 35 women over the words of their one accused rapist. I have committed to trusting their experience, rather than scouring their stories for inconsistencies or putting them on trial. I believe these women, as they should have been believed many, many years ago, and I will stand with them as an ally, whether they reported their rape 30 years ago or last week.

Contrary to what Cosby's defenders want us to believe, the act of reporting a rape does little to change rape culture. It is telling our stories, as many times as it takes, and staunchly and steadfastly supporting other rape and sexual assault victims, that will lead us to a culture where someday it will only take the truth of one woman, not 35, to drown out the lies of one man.